Published May 13, 2021 at 8:23pm.

Story by Misty Jackson-Miller. Photos by Kirsten Chilstrom.

Three years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark ruling on Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized same-sex marriage under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, longtime partners Beau Chandler and Mark “Major” Jiminez sought to obtain a marriage license at the Dallas County Records Building. After being refused the license because they were a same-sex couple, Beau and Major handcuffed themselves together and sat on the floor of the office to protest the unequal treatment of members of the LGBTQ community. For this act of civil disobedience, they were arrested.

Last year, spouses Beau and Major spoke about their experience at a virtual speaker series hosted by the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum. In “Driving the Change,” the two men discussed what it means to take a stand against injustice and the work that still needs to be done. “They are such an incredible couple,” says Mary Pat Higgins, president and CEO of the museum. “We’re glad they chose to share their story with us. They really personalized the fight for gay marriage.”

The Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum was founded in 1984 by Dallas-area Holocaust Survivors. Its mission is to teach the history of the Holocaust and advance human rights to combat prejudice, hatred, and indifference. “Our goal is that, through teaching history, we can help our visitors understand these events and think about the positive impact each of us can have—when we see something wrong, to stand up, say something, do something. Our hope is that people will realize we all have that power.”

Before she stepped into her current role as president, Mary Pat served on the museum’s board of directors and was involved in education at Hockaday School, leading her to “believe in the transformative difference education can make.”

Mary Pat cites two transformative experiences she’s had in her own life, which dramatically changed how she perceived the world around her. She was a junior at an all-white high school when her school district was ordered to desegregate, and she was bussed to a school that was predominately Black, which had been underfunded and neglected for well over four decades. “The neglect and privilege, by contrast, was just so obvious to me,” she says. “The other experience is, as a mom with a child on the spectrum. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the difference a kind word or a thoughtful gesture can make—like sitting with another student at lunch.”

Upstander

/upstander/

Noun

1. Stands up for other people and their rights.

2. Combats injustice, inequality, or unfairness.

3. Sees something wrong and works to make it right.

Kindness, thoughtfulness, doing something, saying something—those are all attributes of upstanders, and inspiring upstanders is the heart and soul of the museum’s mission. In fact, as you walk into the museum, the very first thing you’ll see is a red wall with the definition of “upstander” on it, says Mary Pat, “so you see that definition, and you think, ‘oh, that’s interesting.” As you walk through the exhibits, even amidst the horrors of some of the worst chapters in human history, you’ll find the names of individual upstanders printed in red. “That is very intentional for us,” she says.

The word “upstander” has gained a lot of currency in recent years, ever since Samantha Power coined the term while promoting her 2002 Pulitzer prize-winning book about genocide, “A Problem from Hell.” Upstanders, as opposed to bystanders, are change agents who make a positive difference in the world around them by speaking out against injustice, bigotry, and wrongdoing. At the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum, visitors learn about the four types of people who emerge in moments of tragedy: perpetrators, victims, bystanders, and upstanders. We can all be any of these things at any given time, but it all comes down to choice.

“We all have control over our individual actions,” says Mary Pat, “We want our guests to understand what it means to speak up for others, and why it’s important not to turn a blind eye when you see something wrong.”

Throughout its permanent and special exhibitions, the museum presents a bleak, well-documented history of genocide and human rights atrocities. They pull no punches. In fact, many Texans are dismayed to learn that Stephen F. Austin promoted an unfounded rumor about cannibalism to further dehumanize the Karankawa, which led to sweeping massacres and the eventual annihilation of the native tribe along the southern Texas coast.

The history is straightforward, brutally honest, and punctuated by the first-hand accounts of witnesses and survivors. In the Shoah wing, for example, a restored Nazi-era boxcar that was used to transport Jews to concentration camps now features video testimony of Holocaust survivors who describe the horrors of these trips. However, by highlighting the names of individual upstanders who stood up to the hegemonic machinery of Nazi Germany, often at the cost of their lives, the museum demonstrates how critical it is for individuals to take a stand, because these small acts restore our sense of humanity and reinforce our shared commitment to our neighbors from all walks of life. Mary Pat explains that in many of these instances, “Standing up for others often begins with standing up for yourself.”

The museum also regularly hosts signature programs like the Funk Family Upstander Speaker Series, in which recognized upstanders are invited to share their stories with a wider audience. At a recent event, interfaith activists Mohammed Al Samawi and Justin Hefter spoke about how their connection helped Al Samawi, an al-Qaeda target, get safely out of Yemen in 2015.

At another event, Betty Daniels Rosemond spoke about her lifelong commitment to equal rights for Black Americans. In 1961, she dropped out of college to join the Congress of Racial Equity (CORE) and became a Freedom Rider. She almost lost her life in Poplarville, Mississippi when a violent mob attempted to kidnap and lynch members of her group. Dale Long, another signature speaker, survived the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL. He was 11 years old and has dedicated his life to civil rights ever since.

In addition to the exhibitions and signature programs, the educational team at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum also curates and maintains a library archives of original manuscripts, letters, and artifacts with the goal of preserving these materials for future generations. “We are always broadening our archives,” says Mary Pat, “and collecting those histories and stories.” And among the stories a visitor might come across? The handcuffs that Beau and Major used that day at the Dallas Records Building to protest marriage inequality, donated by the couple so that museum visitors could have a concrete, physical connection to their story.

The juxtaposition of upstanders against the backdrop of genocide and human rights abuses is a unique feature of the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum. Because as you progress through the various historical exhibits, says Mary Pat, “you read about it, you think about it, and it is our hope that people will be inspired to take action and seize the moment. I was nervous that the subject matter would be too wearing, but we’re talking about it in the context of making a difference today, and if we can celebrate that behavior, it then becomes a hopeful experience.”

For more information about special exhibitions and events at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum, visit their website at dhhrm.org. There you can also make a donation to support their work or find out more about how your organization can become a community partner.

More Good Stories

Featured

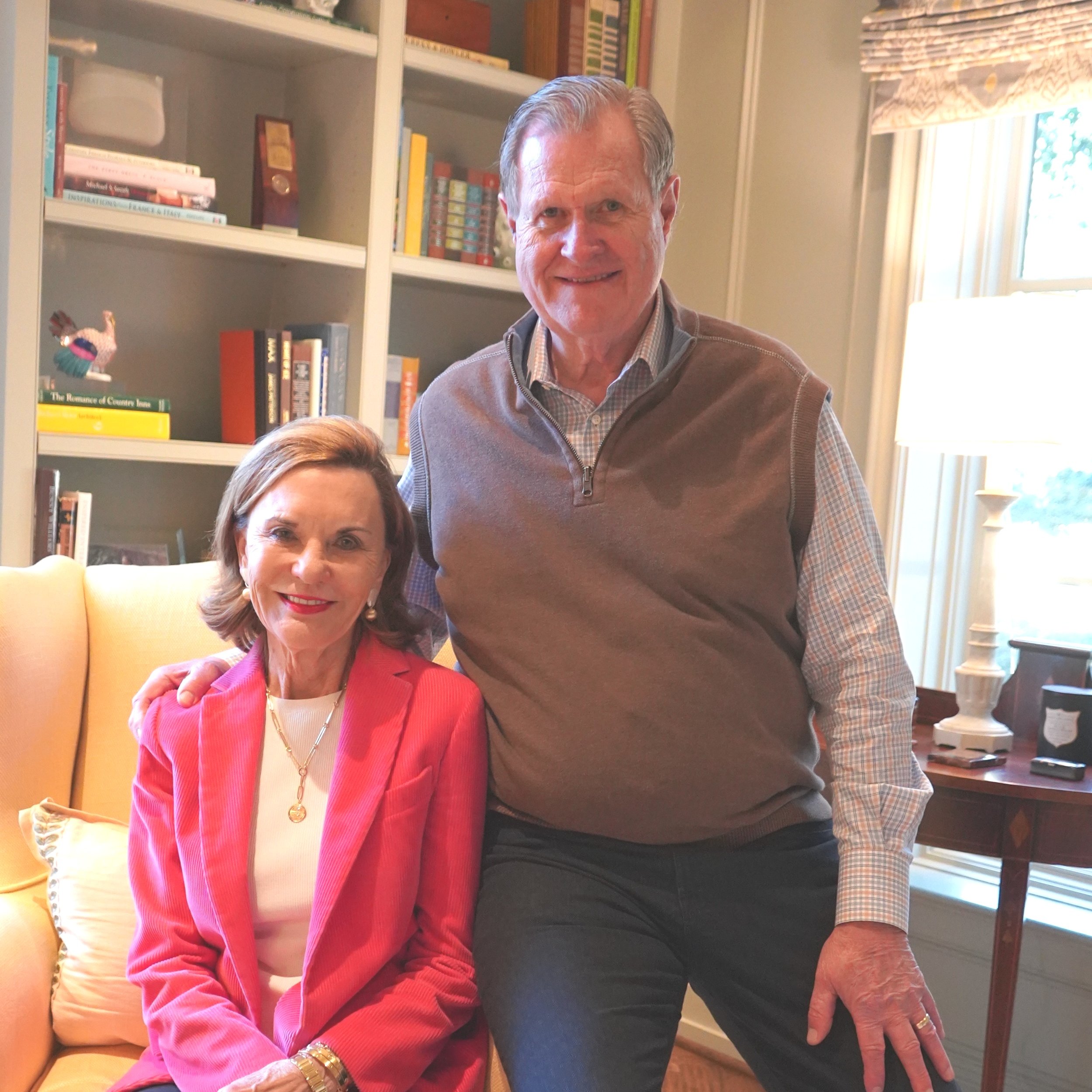

When Kathy and Larry Helm heard about The Senior Source’s 60th Birthday Diamond Dance-Off, they knew they had to put on their dancing shoes! For the Helms, this event combined two of their passions into one. Celebrating and supporting The Senior Source, a Dallas-area nonprofit that has been serving older adults for 60 years, and dancing together, which they have been doing since they were high school sweethearts. Both Kathy and Larry have chaired the board of directors of The Senior Source and have been proud supporters since 1998. It seemed only fitting they should be voted into the finals to dance on stage at Klyde Warren Park this past summer.

In 2020, more than 912,000 women were diagnosed with some form of cancer in the United States alone. During that same pandemic year, countless medical appointments were canceled while people were social distancing, and yet still each day nearly 2,500 women heard the news, “you have cancer.” There is no doubt that these words can be crushing to hear, but what’s equally crushing is the lack of tangible, encouraging support that exists to help women feel beautiful, strong or “normal” before, during and after cancer treatment.

When Tom Landis opened the doors to Howdy Homemade in 2015, he didn’t have a business plan. He had a people plan. And by creating a space where teens and adults with disabilities can find meaningful employment, he is impacting lives throughout our community and challenging business leaders to become more inclusive in their hiring practices.

Have you ever met someone with great energy and just inspired you to be a better you? Nitashia Johnson is a creator who believes by showing the love and beauty in the world it will be contagious and make an impact. She is an encourager and knows what “never give up” means. Nitashia is a multimedia artist who works in photography, video, visual arts and graphic design. Her spirit for art and teaching is abundant and the city of Dallas is fortunate to have her in the community.

The United Nations Association Dallas Chapter (DUNA) honored Rev. Bill and Norma Matthews for their ongoing commitment, helping advance the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals agenda by promoting peace and well-being.